Each parental generation faces tough choices when trying to raise children. Some of the questions remain reassuringly constant.

- What school should my children attend?

- Am I doing enough to help them succeed?

- Is tough love the right approach?

Most of the doubts plaguing parents are timeless; they are a rite-of-passage and every year dozens of books are written (or plagiarised) attempting to explain some new undiscovered-scientific angle.

For instance, in the last few years we have had The Marshmallow Test, based on the Stanford experiment which indicates that kids that can delay gratification go onto better life outcomes. We have also had Grit, which posits that children who can display grit or stickiness at a habit will have much greater success than those that have natural talent but are lazy.

Very little of this is a revelation to parents. The really hard questions are those that exist in media res; the kinds of questions that only apply to the current generation.

Previously it might have been,

- 1960’s: How do I respond if my child is involved in the counter-culture?

- 1970’s: Is the Vietnam War a worthy cause?

- 1980’s: How do I encourage my children to practice safe sex?

- 1990’s: Is around-the-world backpacking safe?

Today, in 2021, the thorniest parental question is;

Should I let my children use social media, in particular, YouTube?

And, honestly, I just don’t know.

I grew up with an analogue childhood and adopted digital technologies in my very late teens. I didn’t have a computer at home; my first computer was a laptop which I purchased for going to University in 2002.

I bought my first mobile phone, a Sagem, at 18 years old. I remember my cousin and I excitedly scratching off the silver foil for the top-up code, inputting it and then wondering what the hell do we do now? We didn’t have anyone to call.

Since that event 20 years ago, mobile devices have become ubiquitous, destroying the home telephony market, the digital camera market and heralding the rise of the tablet.

And, right along side that adoption has been the boom of social media and streaming services.

The glowing rectangle in your pocket lets you broadcast or receive content from anywhere in world. Your written words, images and videos can be shared around the globe instantly. In 2021, anyone can be a content creator; including our children.

It is a brave new world and to be honest, I am not sure I like it. Which puts me into a moral conundrum. I have to ask myself, is it that

Self-broadcasting platforms like YouTube are truly damaging and I do more good by protecting my children from its reach even if they hate me for it?

By denying them I am protecting them from a system designed to turn them into addicts, hooked on the imaginary validation of strangers.

or

YouTube is the democratisation of content and I am just too old to appreciate that it is now the way that younger generations express themselves?

By denying them I am stopping them from an artistic medium.

Well, I just don’t know.

My daughter has performed on stage at the Royal Theatre, Drury Lane in London. I was proud as could be watching her in a production of Newsies; singing and dancing. I watched as the crowd rose to it’s feet, clapping and cheering for all of the cast, her included.

In that any different from seeking the validation of strangers via likes, comments and subscribers?

Ultimately, she was not paid for the performance but on a video platform, she could be compensated for her artistic efforts, potentially leading to greater commercial awareness and business knowledge.

In monetisation terms; it is truly scary just how prevalent YouTube has become.

Little kids are responsible for, quite literally, billions of views on YouTube—pretending otherwise is irresponsible. In a small study, a team of paediatricians at Einstein Medical Center, in Philadelphia, found that YouTube was popular among device-using children under the age of 2. 97 percent of the kids in the study had used a mobile device. By age 4, 75 percent of the children in the study had their own tablet, smartphone, or iPod.

And that was in 2015.

However, internet use was already alarming governmental advisors as far back as 2005. The Byron Report, commissioned in 2008 by Prime Minister Gordon Brown stated that

Many parents do not understand the media, which the Review terms the “generational digital divide”. This can mean that parents are overprotective through fear of what is available.

Parents should be available to assist their children in making decisions about and during use of the media.

It is possible that parental fears about social media are as misguided as other generational fears?

- In late 80’s it was a common fear of parents that sitting too close to the TV would damage a child’s eyesight which was later discovered to be medical nonsense

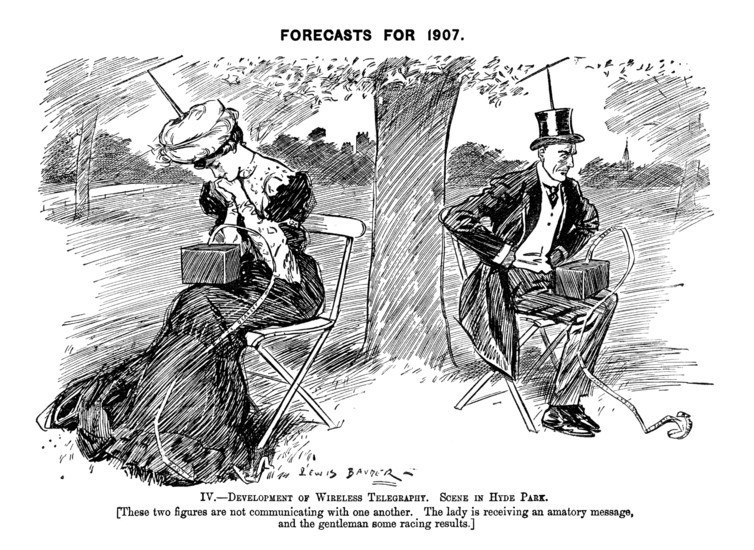

- In 1907 Punch magazine published a cartoon fearing that the radio would prevent couples from speaking to each other

- In the 19th century it was also thought that the telephone would induce deafness

- Experts also believed sulphurous vapours were asphyxiating passengers on the London Underground

- The advent of the moving train was feared to invoke madness, particularly in women

The hesitancy even pervaded Ancient Greece. In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates bemoaned the development of writing. He feared that, as people came to rely on the written word as a substitute for the knowledge they used to carry inside their heads, they would, in the words of one of the dialogue’s characters, “cease to exercise their memory and become forgetful.”

Are these bygone fears any different from articles stating 7 Ways Facebook is Bad for Your Mental Health or Smartphones Make Us Dumber Than Goldfish?

The most widely-quoted example on the internet is Is Google Making Us Stupid?

Loyola University of Chicago professor Steven E. Jones notes, their cellphones all come to life, screens glowing in front of their faces, “and they migrate across the lawns like giant schools of cyborg jellyfish.”

It was an irrational fear of the technological-industrial complex that inspired the Unabomber Ted Kaczynski onto a terrorist rampage sending mail bombs.

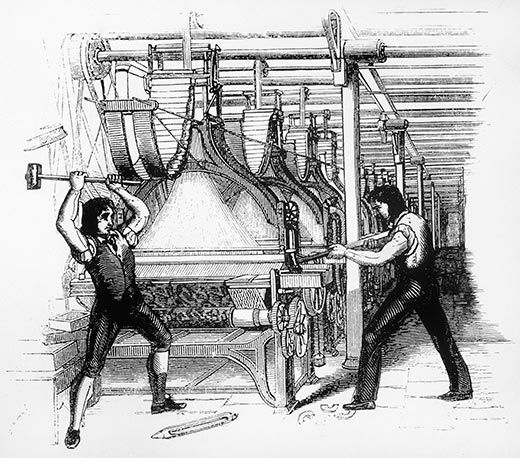

The commonly used term for a person with a fear of technological progress is luddite even though Luddites were highly skilled machine operators.

The Smithsonian Magazine profiled the Luddite movement in great detail in their 2011 article comparing it to modern life. Over 220 years ago, a group of disgruntled factory workers, upset at the lack of work, went on a rampage destroying factories across the Midlands of the United Kingdom.

British working families at the start of the 19th century were enduring economic upheaval and widespread unemployment. A seemingly endless war against Napoleon’s France had brought “the hard pinch of poverty”. Food was scarce and rapidly becoming more costly. Then, on March 11, 1811, in Nottingham, a textile manufacturing center, British troops broke up a crowd of protesters demanding more work and better wages.

That night, angry workers smashed textile machinery in a nearby village. Similar attacks occurred nightly at first, then sporadically, and then in waves, eventually spreading across a 70-mile swath of northern England from Loughborough in the south to Wakefield in the north.

The duality of technology is alive and well today. I am writing this blog post, hosted on AWS and shared via Facebook to friends and family.

College students take out their earbuds to discuss how technology dominates their lives. But when a class ends, Loyola University of Chicago professor Steven E. Jones notes, their cell phones all come to life, screens glowing in front of their faces, “and they migrate across the lawns like giant schools of cyborg jellyfish.”

The original Luddites would say that we are human. Getting past the myth and seeing their protest more clearly is a reminder that it’s possible to live well with technology—but only if we continually question the ways it shapes our lives. It’s about small things, like now and then cutting the cord, shutting down the smartphone and going out for a walk. But it needs to be about big things, too, like standing up against technologies that put money or convenience above other human values. If we don’t want to become, as Carlyle warned, “mechanical in head and in heart”.

It could be that my reluctance of encouraging YouTube as a content platform is masking a deeper, more pressing fear.

I am terrified that my children are not reading enough.

As a child I was a voracious reader; the highlight of the school term was the book fair where piles of shiny new books would be on display. The seller would hand you a catalogue with rows of new titles; accompanied by white tick boxes. Your parents would select the books they were willing to buy and you took the hallowed docket back to your teacher with a brown envelope with money and then a few weeks later the books would arrive.

Rigid new Usborne puzzle books; The Three Investigators, The Hobbit, Hardy Boys, Animals of Farthing Wood and a plethora of other titles by Colin Dann.

If you were feeling adventurous you might have opted for a Jackson and Livingstone Choose-Your-Own-Adventure novel, pencils and die at the ready. Actually, if I am being honest, I much preferred the Fabled Lands series…

For the mature reader there was Point Horror and the excellent Christopher Pike – an author who treated teens as adults. I remember Fall into Darkness and Monster as if it was yesterday. I think I broke the spine of my copy of monster re-reading it so much.

It was an experience. Now, I can barely drag my kids away from Roblox because they see reading as a punishment. When I ask them to pick up a book of their choice they roll their eyes and look longingly at any screen within the vicinity.

The rectangles are glowing orbs of compulsion.

My kids look into screens the way Saruman looks into a Palantir. A slave to it’s power.

However, even now, I find myself questioning, is less reading really a problem for children?

“We are not only what we read,” says Maryanne Wolf, a developmental psychologist at Tufts University and the author of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. “We are how we read”.

Nowadays, my kids surface skim articles online for research and jump erratically from subject to subject, their stream of consciousness moving as quickly as a mouse click on Wikipedia.

It must be! I convince myself. It must be a problem not to read. Then the doubts creep in; is it though?

Isn’t the narrative in computer games just as rich and compelling? How is reading any different from the moral choices they exhibit during the interactive Minecraft game?

The problem is not just children.

Bruce Friedman, who blogs regularly about the use of computers in medicine, also has described how the Internet has altered his mental habits. “I now have almost totally lost the ability to read and absorb a longish article on the web or in print,” he wrote earlier this year.

One of the artforms that I hope my children learn to enjoy is reading the work of playwrights, particularly Shakespeare.

Which is why the YouTube conundrum is so confusing.

Would the Bard today have been a YouTube personality? Would his rallying cry have have been encouraging audiences to Love all, trust a few and smash that subscribe button!

Or, like Aaron Sorkin, would he have hated the internet and all of it’s vacuous simplicity?

I just don’t know.

I suppose that, in order to tackle the YouTube dilemma, we should consider the rise of the moving picture, particularly television.

Television has long been demonised as a corrosive effect on children.

However, fifty years ago, the most influential children’s-television studio in history, Children’s Television Workshop, was invented, thanks to funding from the Ford Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and the United States government. It created a cultural phenomenon —Sesame Street—supported by education experts and Jim Henson, the creator of the Muppets.

Sesame Street was credited with a noticeable rise in child literacy.

It was found that access to the show was associated with improved elementary school performance in “the generation of children who experienced their preschool years when Sesame Street was introduced in areas with greater broadcast coverage.” In the 1980 Census cohort, for example, kids who had access to Sesame Street were “1.5 to 2 percentage points more likely to be at the grade level appropriate for their age.” The study also found that boys, kids who grew up in poor counties, and black children were particularly impacted by access to Sesame Street.

Similar trends have been observed in Finland where children do not start school until they are seven and TV consumption is accompanied by subtitles greatly increasing English literacy.

However, YouTube is most definitely not a new Sesame Street. James Bridle has written extensively about the, quite frankly, bizarre trash that litters YouTube for Kids.

James writes;

The maker of my particular favorite videos is “Blu Toys Surprise Brinquedos & Juegos,” and since 2010 he seems to have accrued 3.7 million subscribers and just under 6 billion views for a kid-friendly channel entirely devoted to opening surprise eggs and unboxing toys.

As I write this he has done a total of 4,426 videos and counting. With so many views — for comparison, Justin Bieber’s official channel has more than 10 billion views, while full-time YouTube celebrity PewDiePie has nearly 12 billion — it’s likely this man makes a living as a pair of gently murmuring hands that unwrap Kinder eggs. (Surprise-egg videos are all accompanied by pre-roll, and sometimes mid-video and ads.)

That should give you some idea of just how odd the world of kids online video is, and that list of video titles hints at the extraordinary range and complexity of this situation.

James goes on to deep dive into the truly disturbing world of YouTube automation which combines keyword analysis with stock footage libraries and pirate content to produce every more strange and recycled animations; some of which take a very, very dark or illegal turn with cartoons such as Peppa Pig eating her father, drinking bleach or being injected.

He adds in an addendum;

This video, BURIED ALIVE Outdoor Playground Finger Family Song Nursery Rhymes Animation Education Learning Video, contains all of the elements we’ve covered above, and takes them to another level. Familiar characters, nursery tropes, keyword salad, full automation, violence, and the very stuff of kids’ worst dreams. And of course there are vast, vast numbers of these videos. Channel after channel after channel of similar content, churned out at the rate of hundreds of new videos every week.

Industrialised nightmare production.

YouTube is still a wild west of content free from the kind of shepherding and investment that led to the rise of Sesame Street.

Do I want my kids exposed to that?

No.

Does that mean I have to ban them from the platform altogether?

I just don’t know.

To allow the kids to create their content would be to expose them to a plethora of exciting digital skills including

- Marketing

- Keyword analysis

- Editing

- Sound production

- Script writing

- Planning

- Collaborating with other friends and creators

- Public speaking

- The list is almost endless…

Is it so different from Steven Spielberg shooting movies at 12 years old or Christopher Nolan borrowing his dads Super-8 camera as a child to remake Star Wars with action figures?

Would our luddite fears of moving pictures have deprived the world of great directors? Or did the faith and guidance of their parents help them navigate a tricky world and, in doing so, create great content?

All of this only serves to bring me full circle back to my parental responsibilities.

Is YouTube a new medium which my children should be free to explore and to harness by creating and sharing new content of their own creation?

Or is it a Charybdis of child attention, pulling them into an exploitative, increasingly automated world which encourages them to shun time dedicated to the more traditional arts?

I just don’t know.